About Me

- Satima Flavell

- Perth, Western Australia, Australia

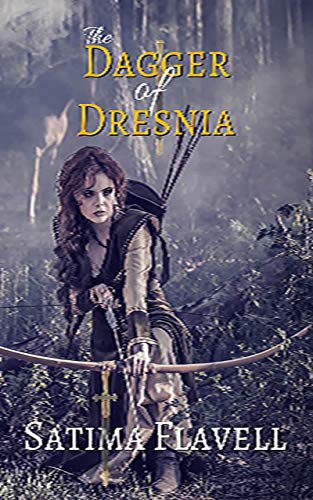

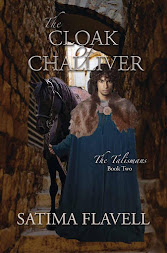

- I am based in Perth, Western Australia. You might enjoy my books - The Dagger of Dresnia, the first book of the Talismans Trilogy, is available at all good online book shops as is Book two, The Cloak of Challiver. Book three, The Seer of Syland, is in preparation. I trained in piano and singing at the NSW Conservatorium of Music. I also trained in dance (Scully-Borovansky, WAAPA) and drama (NIDA). Since 1987 I have been writing reviews of performances in all genres for a variety of publications, including Music Maker, ArtsWest, Dance Australia, The Australian and others. Now semi-retired, I still write occasionally for the ArtsHub website.

My books

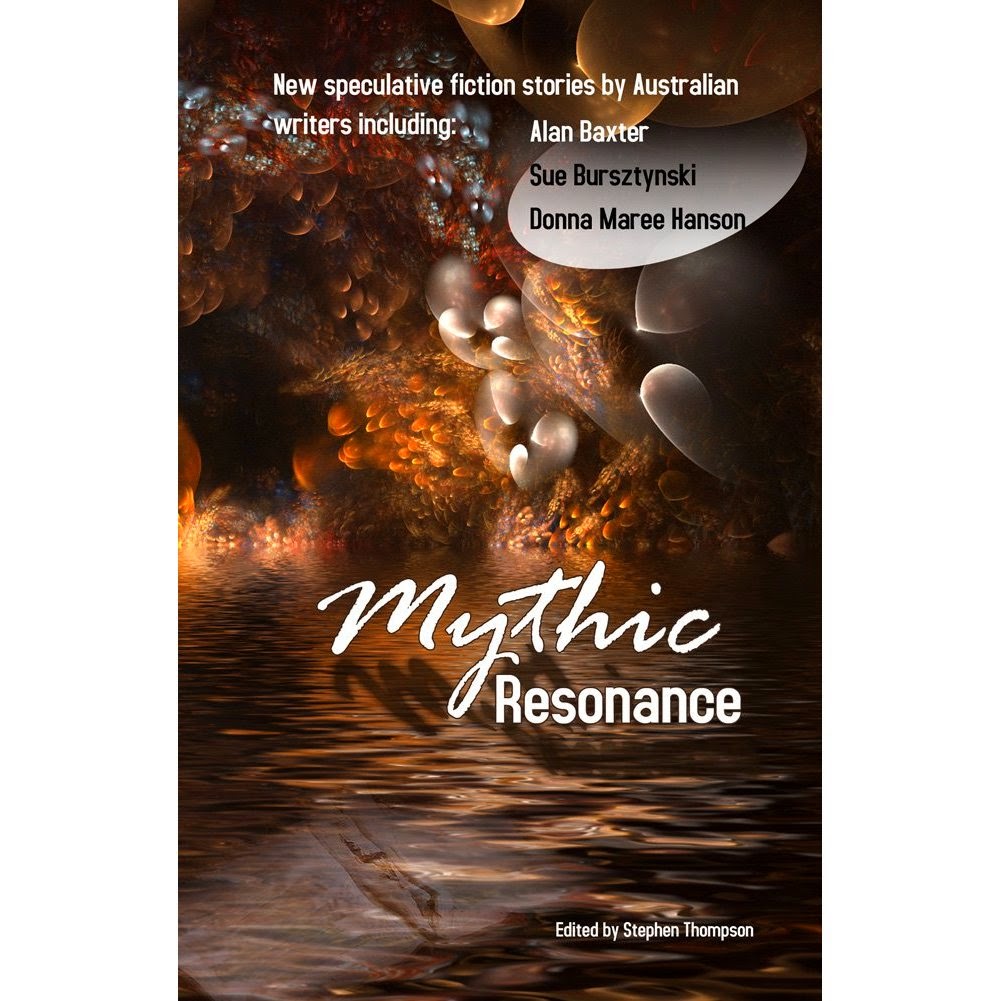

The first two books of my trilogy, The Talismans, (The Dagger of Dresnia, and book two, The Cloak of Challiver) are available in e-book format from Smashwords, Amazon and other online sellers. Book three of the trilogy, The Seer of Syland, is in preparation.I also have a short story, 'La Belle Dame', in print - see Mythic Resonance below - as well as well as a few poems in various places.

The best way to contact me is via Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/satimaflavell

Buy The Talismans

The first two books of The Talismans trilogy were published by Satalyte Publications, which, sadly, has gone out of business. However, The Dagger of Dresnia and The Cloak of Challiver are available as ebooks on the usual book-selling websites, and book three, The Seer of Syland, is in preparation.

The easiest way to contact me is via Facebook.

The Dagger of Dresnia

The Cloak of Challiver, Book two of The Talismans

Available as an e-book on Amazon and other online booksellers.

Mythic Resonance

Mythic Resonance is an excellent anthology that includes my short story 'La Belle Dame', together with great stories from Alan Baxter, Donna Maree Hanson, Sue Burstynski, Nike Sulway and nine more fantastic authors! Just $US3.99 from Amazon.

Got a Kindle? Check out Mythic Resonance.

Follow me on Twitter

Share a link on Twitter

For Readers, Writers & Editors

- A dilemma about characters

- Adelaide Writers Week, 2009

- Adjectives, commas and confusion

- An artist's conflict

- An editor's role

- Authorial voice, passive writing and the passive voice

- Common misuses: common expressions

- Common misuses: confusing words

- Common misuses: pronouns - subject and object

- Conversations with a character

- Critiquing Groups

- Does length matter?

- Dont sweat the small stuff: formatting

- Free help for writers

- How much magic is too much?

- Know your characters via astrology

- Like to be an editor?

- Modern Writing Techniques

- My best reads of 2007

- My best reads of 2008

- My favourite dead authors

- My favourite modern authors

- My influential authors

- Planning and Flimmering

- Planning vs Flimmering again

- Psychological Spec-Fic

- Readers' pet hates

- Reading, 2009

- Reality check: so you want to be a writer?

- Sensory detail is important!

- Speculative Fiction - what is it?

- Spelling reform?

- Substantive or linking verbs

- The creative cycle

- The promiscuous artist

- The revenge of omni rampant

- The value of "how-to" lists for writers

- Write a decent synopsis

- Write a review worth reading

- Writers block 1

- Writers block 2

- Writers block 3

- Writers need editors!

- Writers, Depression and Addiction

- Writing in dialect, accent or register

- Writing it Right: notes for apprentice authors

Interviews with authors

My Blog List

-

Whatcha Reading? April 2024, Part Two - Hello, everyone! I’m back and big thanks to Sarah for driving the Whatcha Reading party bus in my absence. I loaded up my ereader and my Libro.fm app for m...1 hour ago

-

The Shark Is Closed for Queries - Please visit In Memoriam: Janet Reid for more about the late great Shark.6 hours ago

-

New Medieval Books: From Genghis Khan to Tamerlane - A look at how the peoples and states of Central Asia and Persia coped with the Mongol invasions and conquests, ranging from the Ilkhanate to the Timurids. ...8 hours ago

-

A To Z 2024 - Villains! - X Is for eXtras - In all the, the years I’ve been doing the A to Z Challenge, I’ve only had one occasion when I got a real X word - during my Greek Mythology posts. Tha...11 hours ago

-

New Books and ARCs, 4/26/24 - As we hurtle toward the end of another April, there’s still time to tuck in one more stack of new books and ARCs that have come to the Scalzi Compound. Wha...13 hours ago

-

Kathy Stewart books… - Kathy Stewart was a stalwart of Gold Coast Writers some years back and I appreciated her help and support with my writing. She can edit and write up some e...17 hours ago

-

Sometimes You’re a Wedged Bear in Great Tightness - That is, you are stuck. Whether you’re stuck because you got yourself in that situation or because of life circumstances… Being stuck is kind of ho...22 hours ago

-

Unlocking the Moon’s secrets: from Galileo to giant impact - Unlocking the Moon’s secrets: from Galileo to giant impact It is a curious fact that some of the most obvious questions about our planet have been the ha...1 day ago

-

To Tate Britain - and Ellen Terry’s Dress. By Penny Dolan - The iconic portrait of Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth in her beetle-wing dress has been a favourite painting of mine for many, many years. ...1 day ago

-

Samantha M. Bailey - Samantha M. Bailey is the USA Today, Amazon Charts, and #1 international bestselling author of Woman on the Edge, Watch Out for Her, and A Friend in the Da...2 days ago

-

Plotting 101: Top 10 Tips For Crafting Compelling Stories - Plotting Like a Pro One of the most searched-for terms on this blog is ‘help with plotting’. Plot – aka structure if you’re a screenwriter – can be a tri...5 days ago

-

The Great Discworld Retrospective No. 14: Lords And Ladies - After the colossal success of Small Gods, you might think that Terry Pratchett might have wanted to try out some other new ideas. However, given the way th...5 days ago

-

5 Common Problems With Beginnings - *By Janice Hardy, @Janice_Hardy* *If your beginning isn't working, no one will get to the ending.* A novel’s beginning is under a lot of pressure. It has...1 week ago

-

I promised photos from the trip - I feel like a slacker but I have been busy. There’s so much going on, so much to write about. We’ve been back six weeks. It feels like a short time and a l...1 week ago

-

I promised photos from the trip - I feel like a slacker but I have been busy. There’s so much going on, so much to write about. We’ve been back six weeks. It feels like a short time and a l...1 week ago

-

Mastering Blog Post Creation: 10 Essential Steps to Enhance Your Writing Process - The post Mastering Blog Post Creation: 10 Essential Steps to Enhance Your Writing Process appeared first on ProBlogger. It hits you like a TON of BRICKS!...1 week ago

-

Newsletter 16th April 2024 - Here’s a copy of my newsletter from April 16th, 2024. Sign up via my website to get newsletters directly to your inbox (and remember to check your Spam f...1 week ago

-

'The Tic-Toc Boy of Constantinople' in the revered The Conversation as one of five "Australian literary works of particular relevance to national conversations about AI" - I've always respected and admired *The Conversation, *so it is a humbling privilege to have 'The Tic-Toc Boy of Constantinople' written about in *The Con...2 weeks ago

-

Ourselves: 100 Micro Memoirs - I am lucky enough to have a non-fiction piece, ‘Helicopter Parents’, in this new release from Night Parrot Press, Ourselves: 100 Micro Memoirs. This is the...2 weeks ago

-

The Dead Boys Detective Agency. It is a very silly name. But accurate. - April 25th. DEAD BOY DETECTIVES. It's really good -- it's funny, it's smart, it's scary, and it even has a few familiar faces... (And no, you won...3 weeks ago

-

#3 WEP GET TOGETHER - APRIL 2024 - IT'S THE A - Z CHALLENGE! - Hi WEPpers and friends! Already time for out third Get Together. Life is flashing by! Hit us with your news, writerly or personal. We'd love to hear fro...3 weeks ago

-

Henry of Lancaster and His Children - The close bonds which Edward II's cousin Henry of Lancaster, earl of Lancaster and Leicester, forged with his children have fascinated me for a long time...3 weeks ago

-

Urbenville Adventure - Wow, Urbenville, what an adventure! An approach so tough I nearly threw up. Climbs so hard I’m still hurting. Plants so vicious, one grass-spike tore my co...4 weeks ago

-

Researching the birth of the first domestic violence refuge - Read a researcher's journey exploring the first few years of Chiswick Women's Aid. The post Researching the birth of the first domestic violence refuge ...5 weeks ago

-

Trip to Brazil 2024 - Landing in the Megalopolis of Sao Paulo On February 7th I flew to Sao Paulo, Brazil to start a 17 day teachi...1 month ago

-

Photo Parade 2023 - A bit of fun at the beginning of the new year. I’m following several German travel blogs, and that way came across the annual Photo Parade (Fotoparade) on ...3 months ago

-

Happy Public Domain Day 2024, the end of copyright for 1928 works - My annual reminder that January 1st is Public Domain Day, and this year copyright has ended for books, movies, and music first published in the U.S. in 192...3 months ago

-

The White Horse Band - Live Blues/Rock - 31 March 2023 Hi All, Time for some LIVE Video Music from me… (as opposed to my original stuff)…. I got into a blues/rock band for a one off gig at ...4 months ago

-

Konrath Thanksgiving - Black Friday - Cyber Monday Kindle Bundle Sale - *Get all of my ebook box sets on Amazon Kindle for 99 cents each, November 23 - 28.* *THAT'S 33¢ PER BOOK!* Almost my entire backlist of fifty-four ebooks...5 months ago

-

Questions from year 9 students - Recently – actually, not very recently but I somehow forgot to write this sooner – I did what has become an annual online Q&A with the Year 9 girls at Bedf...5 months ago

-

On Ohio, and the novels, and the new class - Just small news here. The new class is finished in first draft, and I’m now (and for the first time ever) doing the complete course bug-hunt and clean-up B...6 months ago

-

Big disruption hit book publishing before AI showed up - Publishers Weekly recently hosted a stimulating and smart online session about AI and publishing, thanks to the organizing and moderating skills of Peter...6 months ago

-

Flogometer 1180 for Christian—will you be moved to turn the page? - Submissions sought. Get fresh eyes on your opening page. Submission directions below. The Flogometer challenge: can you craft a first page that compels me ...8 months ago

-

Storny Weather - I've just been out fixing up the damage from last night's storm. This is pretty much the first time I've been able to spend much time outside and do any...8 months ago

-

Parody - The other day, for the first time in a very long time, I heard the Barbie Song. So, being me, I decided to parody it, in hour of Alianore Audley and *The...9 months ago

-

Parody - The other day, for the first time in a very long time, I heard the Barbie Song. So, being me, I decided to write a parody. Hope you like it! *Hiya, Ali...9 months ago

-

To Live and Love - To live and love for the both of us Ten years ago today I made that vow I've struggled in the decade since Not always knowing exactly how Ten years you've...9 months ago

-

“It’s Random” – a random scribble - “Why am I even here? It’s random. No Divine Thing. No actual “purpose” except what we make of it. I haven’t made anything of it except to be restless, to a...9 months ago

-

#MemorialDay, remembering a female patriot ancestor - *© 2022 Christy K Robinson* We are taught stories about heroic men who gave their lives to bring independence and liberty to their families, friends--and...10 months ago

-

A tale of two titles - I have done something notably foolish. Which is perhaps nothing new, though the circumstances on this occasion are unusual. To whit, I am publishing two bo...1 year ago

-

Poem: If Wishes were horses - A team of horses racing toward me Brown like the uniforms of soldiers fortressing me around Speckled like a found family, salt of the earth Whit...1 year ago

-

another review for the Christmas Maze - *The Christmas Maze by Danny Fahey – a Review by David Collis* Why do we seek to be good, to make the world a better place? Why do we seek to be ethi...1 year ago

-

-

-

Children’s Rights QLD Ambassador - Children’s Rights QLD appointed Karen Tyrrell (me) Ambassador for Logan City, ahead of Children’s Week, 24-29 Oct 2022. I’m an award-winning child-empowe...1 year ago

-

ANWERING THE CALL: LESSONS FROM THE THRESHOLD - NEXT STORY SANCTUARY "Anwering the Call: Lessons from the Threshold" Sept. 20, 7 pm eastern $30 Online Whether you're starting a project, a school year, ...1 year ago

-

The Green House, Chapters 1-4 (Revised) - [Dear Reader: Having refined my intentions for this novel based on a lot of recent thinking about life and art, I have restructured and revised the first f...1 year ago

-

Publishing Contracts 101: Beware Internal Contradications - It should probably go without saying that you don't want your publishing contract to include clauses that contradict one another. Beyond any potential l...1 year ago

-

Tara Sharp is back and in audio book - SHARP IS BACK! Marianne Delacourt and Twelfth Planet Press are delighted to announce the fifth Tara Sharp story, a novella entitled RAZOR SHARP, will be ...1 year ago

-

Website Update - My website www.stephendedman.com has been updated, with details of my latest books; please check it out!2 years ago

-

Non-Binary Authors To Read: July 2021 - Non-Binary Authors To Read is a regular column from A.C. Wise highlighting non-binary authors of speculative fiction and recommending a starting place fo...2 years ago

-

ATTENTION: YOU CAN’T LOG IN HERE - Hey YOU! This isn’t the forum. You’re trying to login to the Web site. THE FORUMS ARE HERE: CLICK THIS The post ATTENTION: YOU CAN’T LOG IN HERE a...2 years ago

-

I'M INSIDE A SHORT STORY!! - Ok everyone, you have to read this very short short story. Firstly because it is good, (check out the Bligh story within it too), but also because I'm ...2 years ago

-

Grandmother Dragon Forever - It feels like centuries since the last time I wrote something for the Dragon Cave. Only something of great importance would drag me out of my retirement...3 years ago

-

-

What communicates power? - Well, I have to say, I wasn't expecting to get this far behind on my reports on the show, but the launch month was very busy, and then the next month turne...4 years ago

-

The Legendary Game Pac-Man Has No Meaning. - [image: The Legendary Game Pac-Man Has No Meaning.] The Legendary Game Pac-Man Has No Meaning. Let's take a look at how this word came about. Actually, P...4 years ago

-

Readers Notice and They Care - Readers care about story details and they care about characters. Both last night and this afternoon I had conversations with readers upset about the way au...4 years ago

-

Review of Verdi's MacBeth (WA Opera) - *Our president, Frances Dharmalingham, has written a critique of a recent visit to the opera: Verdi’s ‘Macbeth’.* At Christmas 2018, my family’s gift to ...4 years ago

-

Breakout 3: tips for engaging your audience - Tips for engaging your audience: how to improve presentation, public speaking confidence and presence on stage, no matter how small the stage is. Present...4 years ago

-

The Trains Don't Stop Here - It's been a long, long time since my last blog post. One of the main reasons for this – apart from life being way too busy in general – is that, in my dwin...4 years ago

-

Portrait of a first generation freed African American family - Sanford Huggins (c.1844–1889) and Mary Ellen Pryor (c.1851–1889), his wife, passed the early years of their lives in Woodford County, Kentucky, and later...4 years ago

-

Revisiting the Comma Splice - One of the difficulties as an editor, particularly when working with fiction, is to know when to be a stickler for the rules. For some people this is not a...4 years ago

-

New releases - SFFBookBonanza - StoryOrigin - SciFi and Fantasy Book Sale - New Releases – Jul 2019 The latest and greatest new releases in Science Fiction and Fantasy books! New releases July 2019 99 cent sale - July 22nd - 28t...4 years ago

-

Assassin’s Apprentice Read Along - This month, in preparation for the October release of the Illustrated 25th Anniversary edition of Assassin’s Apprentice, with interior art by Magali Villan...4 years ago

-

STOLEN PICTURE OPTIONS TELEVISION RIGHTS TO BEN AARONOVITCH’S RIVERS OF LONDON - *STOLEN PICTURE OPTIONS TELEVISION RIGHTS TO BEN AARONOVITCH’S * *RIVERS OF LONDON* *London, UK: 29April 2019*: Nick Frost and Simon Pegg’s UK-based ...4 years ago

-

A Movie That No Writer Should See Alone - Really. REALLY. Trust me on this. particularly since this film, ‘Can you ever forgive me?’, is based on a ‘True story’ – and too many writers will see too...5 years ago

-

Review: Trace: who killed Maria James? - [image: Trace: who killed Maria James?] Trace: who killed Maria James? by Rachael Brown My rating: 5 of 5 stars Absolutely jaw-dropping, compelling readin...5 years ago

-

Dance Photo Shoots - Photo Session Planning & Preparation Have you ever wanted to do a photo shoot for dance but have been a little unsure about how and what really happens? ...5 years ago

-

On Indefinite Hiatus - (Which I pretty much have been from this site for a while already, but for real now.) You can find most archive content through the On Writing page, and li...6 years ago

-

2017 Ditmar Winners Announced - Over the Queen’s Birthday weekend, spec fic fans gathered for Continuum 13: Triskaidekaphilia. Continuum is always a great convention, and this year it was...6 years ago

-

Writing about the Crusades and talking about a "meddlesome priest" - The Middle Ages are in the news again, so here is a roundup of recent news articles. We start with three good reads from historians talking about the crusa...6 years ago

-

The One and the Many – every Sunday - My first serious girlfriend came from good Roman Catholic stock. Having tried (and failed) to be raised as a Christian child and finding nothing but lifele...6 years ago

-

A Shameless Plug Ian Likes: Bibliorati.com - A little-known fact is that I once had a gig reviewing books for five years. It was for a now-defunct website known as The Specusphere. It was awesome fun:...7 years ago

-

Book Review - Nobody by Threasa Meads - Available from BooktopiaThe subtitle for this work is *A Liminal Autobiography*. Liminal: 1. relating to a transitional or initial stage of a process. 2...7 years ago

-

A whole 'nother year-and-a-bit - Well, we have let this blog slip, haven't we? I guess Facebook has taken over from blogs to a very large degree, but I think there is still a need for blo...7 years ago

-

2017 Potential Bee Calendar – & ladybirds and butterflies - Bees on flowers – all sorts of flowers (& bees) – and lady birds and butterflies. There were hundreds (literally) of photos to choose from. This is a small...7 years ago

-

What is dyslexia? - *" **The bottob line it thit it doet exitt, no bitter whit nibe teottle give it(i.e ttecific lierning ditibility, etc) iccording to Thilly Thiywitz ( 2003)...8 years ago

-

Rai stones - *(Paraphrased from Wikipedia)*: Rai stones were, and in some cases are still, the currency of the island once called Yap. *They are stone coins which at th...10 years ago

-

Cherries In The Snow - This recipe is delicious and can also be made as a diet dessert by using fat and/or sugar free ingredients. It’s delicious and guests will think it took ...11 years ago

-

Al Milgrom’s connection to “Iron Man” - Via the Ann Arbor online newspaper - I felt it was worth repeating as a great example of Marvel doing the right thing by a former employee and without the ...13 years ago

Favourite Sites

- Alan Baxter

- Andrew McKiernan

- Bren McDibble

- Celestine Lyons

- Guy Gavriel Kay

- Hal Spacejock (Simon Haynes)

- Inventing Reality

- Jacqueline Carey

- Jennifer Fallon

- Jessica Rydill

- Jessica Vivien

- Joel Fagin

- Juliet Marillier

- KA Bedford

- Karen Miller

- KSP Writers Centre

- Lynn Flewelling

- Marianne de Pierres

- Phill Berrie

- Ryan Flavell

- Satima's Professional Editing Services

- SF Novelists' Blog

- SF Signal

- Shane Jiraiya Cummings

- Society of Editors, WA

- Stephen Thompson

- Yellow wallpaper

Blog Archive

Places I've lived: Manchester, UK

Places I've lived: Gippsland, Australia

Places I've lived: Geelong, Australia

Places I've lived: Tamworth, NSW

Places I've Lived - Sydney

Sydney Conservatorium - my old school

Places I've lived: Auckland, NZ

Places I've Lived: Mount Gambier

Blue Lake

Places I've lived: Adelaide, SA

Places I've Lived: Perth by Day

From Kings Park

Places I've lived: High View, WV

Places I've lived: Lynton, Devon, UK

Places I've lived: Braemar, Scotland

Places I've lived: Barre, MA, USA

Places I've Lived: Perth by Night

From Kings Park

Versatile Blogger Award

Search This Blog

Write it Right: notes for apprentice authors

My speciality as a freelance editor is doing what I call ‘mini-assessments’ for new writers. A mini-assessment is based on a synopsis and the first few pages of the writer’s manuscript. I’ve been doing these for several years now, and it didn’t take me long to realise that a new writer’s problems all show up within a few pages. I quickly learnt, too, that almost all beginning writers show the same six faults. They don’t all have all of them, but I’ve yet to have a newbie client who didn’t show at least three!

I believe the first two are inexcusable, but you’d be amazed at how often I see them! But before getting down to the nitty-gritty, I’m going to give you the standard lecture. It’s quite possible that you already know these things, but it’s surprising how many writers do not, so I always restate them to be on the safe side.

1. It’s extremely hard to get a novel published, and it’s getting harder and harder with the current uncertainties of the economy and the radical changes that are inevitable in the publishing industry. For every thousand MSS sent to publishers, no more than a half-a-dozen are published. Hard SF – or even ‘soft’ SF – is harder to sell than Fantasy and even harder to sell than the most popular genres, Romance, Crime and Mystery.

2. Because it is so hard to get published, your work needs to be of a very high standard in every department. This usually means spending money on editing and/or MS assessment, and these services are not cheap. Because of that, it’s sensible to make sure you’ve done absolutely all you can with the work before handing it to an editor.

3. You may well decide to self-publish. Here are a couple of things to bear in mind.

• ‘Vanity’ publishing should be avoided at all costs. Publishers who want money from you to publish your novel are vanity publishers, even if they call themselves self-publishing houses. True self-publishing means you set yourself up as a publisher and engage your own sub-contractors for editing, artwork, layout and printing. It’s a lot of work, but it usually works out cheaper than vanity presses. In either case, distribution and marketing fall to the author, and it’s a sad fact that most self-published or vanity-published fiction books sell fewer than 100 copies, and many sell fewer than twenty. The bolding there is deliberate as it’s something every wannabe author should know and accept.

• A note on e-publishing. This is becoming more and more the route most writers will follow to get their work ‘out there’. A quick look at Smashwords on any given day will reveal that several dozen new books have miraculously appeared overnight! So it’s just as competitive as the hard-copy market. All those books begging to be read — no one could possibly read all of them, and many readers still have a resistance to reading on-screen at all. So an e-book has to be outstanding to succeed, and the author must also be ready to undertake a lot of work on promotion through the social media. Just sticking your book up online will not by itself bring in sales.

I hope I haven’t put you off writing with the above comments, but I like to make sure new writers don’t have stars in their eyes and are not on the road to being conned by vanity publishers! There are some veritable sharks about on the internet. I’ve heard of people paying as much as $25,000 to get a book published, because they didn’t know any better!

So, back to the six inevitable problems of new writers

1. The first one is not reading enough. A writer learns the basics of the craft by reading work by experienced authors and emulating them. You need to read widely, not just in your preferred genre, but in other genres as well. And it’s important that you read not just modern works, but the classics of past years, too. If a client writes but doesn’t read it’s screamingly obvious to me, and it will be to an editor at a publishing house, too. So make sure you read extensively – non-fiction as well as fiction – and read other genres as well the one you write in. And when choosing books to read, be sure to at least sample the work of authors from days gone by. In any job, the historical perspective is important. If we can’t see where we’ve come from, we’ve got Buckley’s chance of knowing where we are going! But we need to read the modern writers too, so we can start to recognise trends.2. You learn a lot by reading, but it’s not enough to turn you into a writer. The second problem of beginning writers is not bothering to learn the craft of writing.

I don’t know why it is, but many people seem to think that because they know how to write words and sentences, they will automatically know how to write stories, too. Sadly this isn’t true. It takes at least ten years to train as a concert pianist, and it takes about the same amount of time to learn to write well. Just as if you were learning a musical instrument, you need to practise and take tuition, so I hope you wannabe writers out there are doing a bit of writing every day and also going to classes and workshops as often as you can. It’s also useful to join writers critiquing groups, and go to conventions. There are state and national conventions for Romance and Speculative Fiction every year in Australia, and perhaps Crimescene, a relatively new convention held in Perth for readers and writers of crime, suspense and mystery, will set the ball rolling for those genres as well. If you write fiction – especially literary fiction or ‘mainstream’ fiction – you will love the writers festivals that are held annually in most state capitals. Just Google.

The above two faults are inexcusable because all these things can be read online and mastered with practice. All you have to do is Google!

However, the other four faults are excusable, and are readily overcome with time, patience and practice. Here they are:

3. A problem shared by most beginners is not knowing where to start the story. In genre fiction, it’s essential to start, as the Latin poet Horace put it, in media res – right in the thick of things. Beginners tend to load the first few pages with backstory, and that is a sure mark of an amateur. While an already established author might get away with a slow opening, most of us will not. Start with something exciting that leads us to the precipitating incident – the event that gets the story going. We should meet the protag in the first paragraph and know what he or she is seeking within a few pages. This is shown through the precipitating incident. The story then unfolds through a series of disasters that create change within the protagonist so that by the end of the story we see what the character learns about him/herself and the world as a result of the experiences s/he has undergone.

4. And that brings me to structure – another bugbear for beginners. Structure is complex and it’s a thing you learn slowly as you get the knack of producing books. First of all, just bear in mind that for a novel, novella or short story to work you must be able to answer the following four questions:

a. Who is your main character?

b. What does s/he want?

c. What is stopping him/her from getting it?

d. How does s/he deal with the opposition?

These are the four essentials of a good story. If what’s written can’t be summed up in this way, it’s not a story. It might be a lovely descriptive piece, a dissertation, or a clever bit of propaganda, but it’s not a story. These four essentials are also the foundations of a good synopsis. A decent synopsis is an essential part of your submission package. For more detail, see my article on synopsis writing at: http://satimaflavell.blogspot.com.au/2013/03/write-decent-synopsis.html.

A genre novel needs to be constructed, like a play, on a three-act model. However, it should also contain four sections. These two sets of divisions lie parallel and both are essential. This sounds complicated, but it’s one of the things a writer needs to understand.

1. The three acts should cover what some people call ‘three disasters and an ending’:

The three disasters are preceded by what’s called ‘the precipitating (or inciting) incident. This should occur as close to the opening of the book as possible — always quite early in Act 1.

a. The first disaster corresponds to the end of Act 1 (about ⅓ of the way in).

b. The second disaster is the mid-point of Act 2 (about half-way through the novel)

c. The third disaster, the main climax, is the end of Act 2 (about 85 to 90 per cent of the way into the novel. (Act two is easily the longest chapter!)

d. Act 3 – the ending – corresponds exactly to the denouement (see below), which wraps things up. It should take less than 15% of the novel, and is quite often only about 10%.

2. Parallel to this three act structure we have the four classical divisions:

a. Exposition: Allow about 10% of your novel for the exposition, including the precipitating incident.. This section shows the reader ‘who’, ‘what’, ‘where’ and ‘when’. (The ‘how’ is shown in the rising action.)

b. Rising action: This takes up a good 75% of the novel – about ¾ of Act 1 and all of Act 2.

c. Climax: Here we find the main disaster, mentioned in the three act structure, which happens at the end of Act 2.

d. Denouement: As we’ve seen, the denouement corresponds to Act 3, the tail end of the novel. This section is usually very short.

Note: If possible, introduce all your major characters in the exposition. Certainly it’s a mistake to introduce a new major player after about a third of the way through as readers will not usually bond with a latecomer. (Minor characters, of course, are another matter and can be introduced as needed by the plot.)

The precipitating (or inciting) incident comes early in the piece, certainly not more than 10% of the way in. At about the 30% mark should come the protagonist's first setback, which marks the end of Act 1. (All major characters should have been introduced by the end of Act 1, by the way!) Act 2 is the longest act, and it can take up to 60% of the novel. About half way through the total length we should have a second setback, and at the end of Act 2 – 90% of the way through the novel – we have the third and biggest setback. There will have been minor disasters in between, of course, both in the main plot and in the subplot, but the one at the end of Act 2 should show us the main character hitting an all-time low from which he or she has to turn things around. In most novels, this will be where the protagonist’s fortunes turn: the battle is won, the throne is gained, the princess is rescued — or your detective solves the case and confronts the criminal, or the lovers plan a happy future. Then, in true Hercule Poirot style, we should see the main character clear up loose ends. This denouement should use up no more than 10% of the total word count.

5. The fifth problem of beginners is not having sufficient grasp of ‘show, don’t tell’. This is the most widely touted rule in writing, so I’m sure you’ve heard it before, and you will no doubt hear it again and again if you keep on writing.

What ‘show-don’t-tell amounts to is this: when we go to a new place, we learn about it by finding our way around and listening to what the locals have to say. So too, in reading fiction, we learn about the author's world by becoming immersed in the sights, sounds and senses of the inhabitants, who are brought to life through narrative and dialogue. This is especially important these days because modern readers expect an immersion experience. Writers today have to compete with many other forms of entertainment, and most of those are visual.

We cannot give our readers visuals in a straight novel, but we can give them something better. We can get right inside the mind and body of our main character, showing how anger affects his body rather than telling the reader he is angry; showing how he interacts with his world rather describing the scenery or telling us it’s a fine sunny day. Done skilfully, this not only drags the reader into your characters’ world, but also gives the reader information about the characters and the plot. It’s a very subtle thing, this show-don’t-tell. Chekhov put it very nicely when he said, ‘Don’t tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of moonlight on broken glass’. Can you see how that single phrase shows us that it’s night time, the moon is shining, and that the presence of broken glass means there must be a building or some other human artefact nearby, and that there has been an accident or violence or a natural disaster of some sort. In that one little phrase ‘the glint of moonlight on broken glass’, there lies a world of writerly wisdom.

In fact, my friend Carol Ryles came up with a good way to think of the best form of worldbuilding. See it as a picture painted on glass. You then smash that glass picture and insert shards of it – tiny shards, no more than slivers – into dialogue and in action beats (of which more later). There are lots of subtleties in show-don’t-tell, and it’s closely bound up with worldbuilding and point of view. As Chekhov has done, you have to try to make each word carry meaning well above its customary workload in conversation. Can you see how much we learn from ‘Moonlight glints on the broken glass?’ That’s show-don’t-tell at its best.

Fellow author Garry Smailes has written a more in-depth article on 'Show, don't tell'. You can find it on his BubbleCow blog - well worth a look.

6. This strong connection that binds show-don’t-tell to worldbuilding and point-of-view brings me to the last problem of beginning writers – and that’s not having a good enough grasp of point-of-view (POV). I’m assuming you know the difference between first and third point-of-view. First is easier than third in some ways, and harder in others: easier because you have only to write from within the headspace of the main character, and harder because you are limited to that one viewpoint. First person also makes it easier to give readers the immersion experience they want. That’s harder to do in third person. What many authors today do is write from a ‘close third’ (AKA ‘tight third’ or ‘deep third’) viewpoint, which involves getting inside the character’s head just as you would with first person, so you are limited by what that one character thinks, feels, senses and experiences. But in third person you are at liberty to include more than one view point. Do make sure, though, that you only use one POV per scene. ‘Head-hopping’ – skipping about from one character’s head to another – is not only confusing for your readers; it also prevents you from giving them the full immersion experience of the tight third POV. In a really deep third, you write everything, even the narrative, from within the character’s head. You avoid using dialogue tags as much as possible, and you slip in information about the characters and their world where appropriate, always from within the thoughts, feelings and experiences of the POV character. You, as the author, are hidden by the point of view. Your ‘voice’ becomes the voice of the character.

A few pointers on the craft of fiction writing

Do make sure you have a good grasp of the basics, the stuff you learnt in school. Without a good understanding of grammar, spelling, syntax and punctuation you are going to find it impossible to find an agent or a publisher, and if you self-publish a badly written book it simply won’t sell. There are so many self-published books out there that you have to be at least as good as traditionally-published authors if your work is going to attract readers. Learning to lay out your MS like a professional – with wide margins, double-spacing and so on – is also important if you don’t want your submissions to look amateurish. Be sure to read the publisher’s guidelines before preparing your submission, because they do vary in their requirements and expectations. Whatever the instructions for submission say, stick to them exactly. If they ask for a handwritten MS in green ink on pink paper, that’s what you send them!Tighter writing

Avoid unnecessary words, especially adjectives and adverbs! They use up precious space without being very useful. If you feel a noun needs an adjective to describe it, look for another noun that can stand on its own. And if a verb seems to need an adverb, look for a stronger verb.An example of lazy writing:

Jack walked slowly down the highway. It was a really hot summer’s day and he was starting to sweat. He was very thirsty, too. He noticed a little house a few hundred metres away and wondered if he should stop and see if they would give him a drink of cold water. But what if they called the police?

Here is the same mini-scene, written more tightly:

Jack trudged down the highway, the summer sun at his back and sweat pouring down his face. Gods above, it was hot! Maybe he should risk a stop at the cottage that topped the next rise.

Not only have we fewer words in the second example, but a closer relationship with Jack, and a higher degree of tension. In the first example, we are flies on the wall, watching what’s going on. In the second, we are right inside Jack’s body and mind, and we get a better feeling for what he is experiencing.

A few words on dialogue

Dialogue is essential in a genre novel, for many reasons. It furthers the plot, helps slip in information about the characters and their world, and creates a break from narrative and the characters’ internal monologues. These three elements need to be in balance. There is nothing worse than long slices of a character’s internal musings followed by an equally long stretch of description. Break these up with dialogue. Try to have some dialogue on almost every page. Actually, another reason dialogue is important is to break up the appearance of the page by allowing for short paragraphs!But make sure your dialogue is always in character and serves more than one purpose. Use tags (‘he said’, ‘she asked’, ‘Fred replied’ etc) sparingly. If only two people are talking, you only need one tag in about every five lines.

And the tag need not be one of the standard dialogue tags above – and no, I’m not suggesting you use tags such as ‘he growled’ or ‘she opined’ – they are distracting and if overdone, a tad ridiculous. ‘Said’, asked’ and ‘replied’ are usually all you need, although people do occasionally call, shout, or gasp, and words like those are fine in their place. But for heaven’s sake avoid things that aren’t ways of speaking, such as ‘he smiled’, or ‘she frowned’. Facial expressions are not speech tags!

But what I’m really trying to get onto is the topic of ‘action tags’, sometimes called ‘action beats’. An action beat is when we indicate which character we’re focussing on by mentioning what they are doing. Look at this example, which mixes up the three forms of dialogue we’ve just looked at:

As they lay together in the afterglow of love, she snuggled into his arms. ‘Dearest, I want to ask you something.’

He turned his head and brushed her forehead with his lips. ‘Ask away, my sweet.’

‘Would you mind if your mother were to teach me magic?’

Beverak turned onto his side and disengaged the arm that had rested under Tammi’s shoulders. He half pushed himself up and gazed down on her. ‘What? Tammi, you can’t be serious!’

‘Of course I’m serious.’ Tammi’s gaze met his with something like a challenge lurking in their depth. 'It’s part of my heritage.’

‘Part of your heritage? What on earth is that supposed to mean?’

‘The same as it means to your mother and to your cousin Ruthvard. It means I am part-elvish and I have inherited some of the skills that make elves different from ordinary mortals. It means that I might be able to develop those skills in a way that will serve you and Dresnia and the Islands.’

You can see, can’t you, how I’ve used action tags and no tags at all? Not once have I used the words ‘said’, ‘asked’, or ‘replied’.

However, if there are more than two speakers, you can’t get away with no tags at all. Here’s an example with three speakers, in which I’ve used both speech tags and action beats:

Wulfrin appeared from beneath the overhang that served as a goat shed, carrying two small milk buckets. ‘Just finished milking,’ he called. ‘Want some?’

‘You’re late this morning, Wulfrin.’ Auberin’s voice was reproving and Jedderin grinned surreptitiously. Won’t stand any slacking among the servants, won’t his highness.

Wulfrin was unfazed. ‘Sorry, Auberin. Molly was kidding and I had to help her, so I didn’t get to do the milking before breakfast. She’s had a nice little doe kid, another milker for the year after next.’ He disappeared into the kitchen cave, where he could be heard pouring the milk into the vat.

Fiersten yawned. ‘A new goat. How exciting. What a shame we won’t be here to see her grow into a milker.’

‘Thinking of leaving us already?’ Jedderin asked. I wish you’d leave today, you slimy toad.

Fiersten shrugged. ‘To be honest, I’m finding the lessons tedious. All this starting again at the beginning is boring. Besides, the Mistress’s silly celibacy rule is driving me barmy. I’m not used to going without female company. Close female company, I mean, not just listening to Maverill’s prattle about her latest spellcraft experiments.’

Those samples are from my own work (The Dagger of Dresnia, Satalyte Publishing, 2014) and better authors than I will do it better. But as examples of using action beats, dialogue tags and no attribution at all, they serve the purpose well enough.

And more on Point-of-View

As we’ve seen, in constructing a story, we need to have, first and foremost, a character who wants something. This main character should be introduced right at the start and we should learn his or her name in the first paragraph. By the time we’ve read a page or two, we should know what it is that s/he wants. Our main character will carry the POV all or most of the time.Modern readers, especially young ones, don’t want to be told a story; they want an immersion experience. Remember that people today are used to absorbing fiction through TV, movies and video games, where they can see things through the character’s eyes. So, as writers, we have to get inside that character's mind and body and experience his or her world through his or her five senses. Being a fly on the wall and reporting what's happening from the outside will not engage a reader these days.

A friend sent me a quote which is very relevant to the relationship between POV and ‘Show, don’t tell’. It comes from How Fiction Works by James Wood (Picador: New York, 2008). It might be a book worth buying. In this excerpt, Wood is discussing the handling of inner monologue in fiction.

a. He looked over at his wife. ‘She looks so unhappy,’ he thought, ‘almost sick.’ He wondered what to say. This is direct or quoted speech (‘“She looks so unhappy,” he thought’) combined with the character's reported or indirect speech (‘He wondered what to say’). This is the old-fashioned notion of a character's thought as a speech made to himself, a kind of internal address.

b. He looked over at his wife. She looked so unhappy, he thought, almost sick. He wondered what to say. This is reported or indirect speech, the internal speech of the husband reported by the author, and flagged as such (‘he thought’). It is the most recognizable, the most habitual, of all the codes of standard realist narrative.

c. He looked at his wife. Yes, she was tiresomely unhappy again, almost sick. What the hell should he say? This is free indirect speech or style: the husband's internal speech or thought has been freed of its authorial flagging; there is no ‘he said to himself’ or ‘he wondered’ or ‘he thought’.

Note the gain in flexibility. The narrative seems to float away from the novelist and take on the properties of the character, who now seems to ‘own’ the words. The writer is free to inflect the reported thought, to bend it around the character's own words (‘What the hell should he say?’).

We are close to steam of consciousness, and that is the direction that free indirect style assumed in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries:

d. He looked at her. Unhappy, yes. Sickly. Obviously a big mistake to have told her. His stupid conscience again. Why did he blurt it? All his own fault, and what now?

You will note that such internal monologue, freed from flagging and quotation marks, sounds very much like the pure soliloquy of 18th and 19th century novels.

(James Wood is a staff writer at The New Yorker and a visiting professor in English and American literature at Harvard.)

Note from Satima: As you may know, the earliest users of FID (free indirect discourse) included Jane Austen and Gustave Flaubert, so we have come full circle. The current fashion for a tight third POV comes very close to FID, if not SOC (stream of consciousness). To give your work a chance in the current market, it might be wise to adopt a style of inner monologue that comes close to these two styles. Can you see how much closer we are to the character in the last example, and how much we have learnt about him? We are not told that he has something on his conscience: we simply absorb it through his thoughts. We can see he’s prone to self-blame as well.

If we wanted to get all that info in when using the detached style of the first and second examples, we’d end up with something like: ‘He looked over at his wife. ‘She looks so unhappy,’ he thought, ‘almost sick.’ Only the day before, he had blurted out what was on his mind and now his wife was so upset he had no idea what to say. He blamed himself because what he had let slip was really only to assuage his bad conscience.’

Fifty-two words as opposed to thirty-one in Wood’s example d., which is more in the style we should be aiming for.

Food for thought:

‘Show-don’t-tell’ is far more complex than it first appears. Narrative, setting and point-of-view are a kind of holy trinity, each one different manifestation of ‘show-don’t-tell’.What now?

I strongly suggest, if you haven’t already done so, that you join a writers group or a class, either face to face or online. These can be found in all large towns and cities. For example, there are three writers centres in Perth, Western Australia: Tom Collins House, the Peter Cowan Centre and the Katharine Susannah Prichard Writers Centre. You can find all these by Googling. Membership is not expensive and most of the workshops and groups are reasonably priced.You can also learn a lot about the industry as well as the craft of writing by reading blogs by writers, editors and agents. Don’t be scared to leave polite comments, and if time permits, why not start a blog of your own, too, if you don’t already have one? It’s never too early to start getting your name ‘out there’. But refrain from commenting on subjects you know little about as that will just get people’s backs up, and it’s really important to make friends, not enemies, of your fellow writers. Writers are usually very friendly and helpful, and they are also readers who might eventually buy your book!

I wish you all the best in your writing career. Write because you want to, not because you want to make money or win awards. Those rewards are only bestowed on a lucky few: the rest of us have only the joy of writing and hopefully, having a few people like and appreciate what we have written.

It has been a pleasure to share the joy of writing with you. Write on!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)